COVID tracking troubles yield confusing counting

Last updated 11/10/2020 at 10:53pm

According to the count released Nov. 9 by the Orange County Emergency Management Office, the death toll in the county from this year's COVID-19 pandemic is 42 residents.

According to the Texas Department of State Health Services on Nov. 8, Orange County has had 47 COVID-19 deaths.

According to a statement put out by the West Orange-Cove school district in early October, three or more players on its high school volleyball team had tested positive for COVID-19, forcing the school to close the high school campus for two weeks.

But, according to reports filed by WOCCISD with the Texas Education Agency and posted on the DSHS website Nov. 8, West Orange-Cove is reporting that only two high school students involved in on-campus activities – presumably including sports – have tested positive.

Which counts count? Which are correct?

Maybe all of them, based on ever-changing record-keeping standards that have been utilized since the global pandemic hit the United States earlier this year.

Of course, they call it the new coronavirus for a reason. It's new and didn't come with a rule book. People are doing the best they can in weird circumstances.

"The whole thing is messed up for reporting," Orange County Judge John Gothia said recently.

"Doctors, public health departments, emergency centers, they all get to operate under separate rules. But who turns in recoveries?"

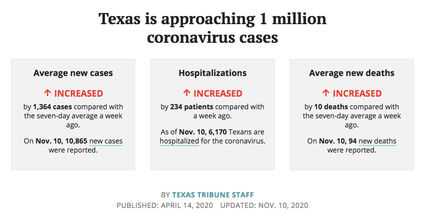

At a time when the state of Texas and the country is setting records for new cases and nearly a quarter of a million Americans have died from the virus, paying attention to numbers seems important, but it's hard to spot trends if they keep changing the measuring sticks.

The DSHS "dashboard" of COVID-19 numbers for Texas, used by many national news and science websites for Texas numbers, showed that Orange County had 450 active cases as of Monday. The latest numbers posted by Orange County as of Monday – a report dated Nov. 3 -- showed 904 active cases.

Tuesday, Joel Ardoin, emergency manager for the county, told Commissioners Court that the state had sent two epidemiologists and one doctor to work out of the Expo Center and clean out a backlog.

That said, the COVID-19 report Ardoin issued to county leaders for Nov. 9 had only 236 active "confirmed" cases, confirmed meaning those individuals that recently tested positive by a PCR (nasal swab) test. People who have positive antigen tests are considered "probable," the county says on its emergency management Facebook page. It says no antibody tests are included in the case count.

The biggest shift in the county's numbers came in the number of deaths. Orange County's official COVID-19 death count stood at 35 for more than a month. The death count kept by the state exceeded the county-released count by more than 10 for much of that month.

"If COVID is listed as the cause of death, we list them, and we assign their death to the county that matches their address," explained Lindsey Rosales, a spokesperson for the DSHS.

Because Orange County does not have its own public health department, so Sharon Whitley, Hardin County's health department director, has had oversight on the reporting passed on to Ardoin, Gothia and through them, the media.

She operates under different rules than DSHS regarding reporting deaths.

"The difference between us reporting 35 deaths and DSHS reporting 45 deaths is that we wait until we get the state registry," she said. "The state is the one to determine if it's COVID-related."

But there's another big difference.

"If someone's in a nursing home and they go to a hospital in Beaumont, your death is counted where you pass," she said.

Of course, Orange County has no hospitals. Anyone dying in a hospital in Beaumont, Port Arthur, Lake Charles or any other city may be getting counted as a resident of another county for COVID record-keeping purposes.

And it leaves open the possibility that a person could show up on one county's positive test count and another's fatality count.

And, as Gothia asked, who's keeping track of recoveries?

"They tell you to isolate for 10 days and then if you have no symptoms and two negative tests on back-to-back days, you're free to go back to work," said Gothia. "But nobody gets tested unless their jobs require them to. After 10 days, you're considered to be cured."

Gothia had COVID-19 in July but subsequently tested "negative" several times, being cleared to appear with Gov. Greg Abbott and President Donald Trump at media events after Hurricane Laura in August.

Which brings us to COVID-19 reporting in schools, most of which started their 2020-21 school year just before or after Laura hit.

According to the latest post on the DSHS website of information the schools turned in through the week ended Nov. 1, Bridge City has had seven high schoolers, one elementary student and five adult staffers test positive since records began being submitted in mid-September for a total of 13 COVID-19 cases.

Little Cypress-Mauriceville's district reports a total of 24 cases during the six weeks reported (one middle schooler, 13 high school students and 10 adults). Orangefield shows 27 cases over the same time period (12 high schoolers, 15 adults) and West Orange-Cove 20 (2 elementary students, 2 middle schoolers, 2 high schoolers and 12 adults).

Vidor ISD was not surveyed for this story, but Gothia used a Vidor example to show how COVID-19 could upset things in a school.

"At one point, Vidor ISD had one principal out and two to three vice-principals out because they'd been around a student that tested positive," he said.

Of course, learning at home has been a statewide failure.

Faced with widespread reports of students failing and missing classes, the state (TEA) announced over the weekend that students falling behind in online-only classes could be forced to return to campus or move to another district.

The TEA said districts now can deny virtual instruction to children with an average grade of less than 70 in their classes or at least three unexcused absences in a grading period.

Locally, most students are attending class in person and the on-campus numbers really went up when parents and students were allowed to change their preferences after the first six weeks.

In Orangefield ISD, for instance, about 19 percent of students signed up for online learning the first six weeks, but only 9 percent chose to continue online for the second six weeks.

Why the school and TEA numbers don't always match up with the numbers students and teachers may report to friends and family probably has something to do with reporting requirements.

The TEA says cases in their reports are defined as any staff member or student who participates in any on-campus activity that is test-confirmed COVID-19 of which a public school is notified.

Reports are to be sent to the state weekly and the new ones are posted on Thursday afternoons.

"The dashboard that you're looking at on the DSHS website, basically that is a statewide look at aggregate COVID reporting," said a TEA spokesman. "It allows us to analyze trends at the state level weekly."

Reader Comments(0)